- Join 11.2K other subscribers

-

Recent Posts

- Know Your Natives – Texas Toadflax May 20, 2024

- Know Your Natives – Harvey’s Buttercup April 25, 2024

- Know Your Natives – Yellow Honeysuckle March 25, 2024

- Know Your Natives – Hooked Buttercup February 27, 2024

- Know Your Natives – Blunt Lobed Woodsia January 19, 2024

- Know Your Natives – Hop Hornbeam December 29, 2023

- Know Your Natives – Ozark Sunflower November 22, 2023

- Know Your Natives – Sweet Coneflower October 29, 2023

- Know Your Natives – Common Evening Primrose October 2, 2023

- ANPS Fall 2023 Meeting August 19, 2023

Categories

Archives

Meta

Category Cloud

Field of Prairie Blazing Stars

Posted in Native Plants, Wildflowers

Tagged Asteraceae, Liatris, Liatris pycnostachya, Prairie Blazing Star

Leave a comment

Invitation to the Arkansas Native Plant Society Fall Meeting

Scarlet Rose Mallow (Hibiscus coccineus) The flower pictured is from a plant purchased last fall at the Arkansas Native Plant Society (ANPS) Native Plant Auction. If you are looking for native plants that are hard to find, this is the place for you! Picture by Mike Weatherford

ARKANSAS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY

FALL 2014 MEETING & PLANT AUCTION

October 10-12, 2014

TEXARKANA, ARKANSAS

The fall meeting of the Arkansas Native Plant Society (ANPS) will be held in Texarkana, Arkansas with field trips to surrounding parks and natural areas. Please plan to join us as we tour some of the unique habitats of the West Gulf Coastal Plain, including chalk woodlands, blackland prairies, and sandhills.

HOTEL AND MEETING LOCATION

Holiday Inn Express and Suites Hotel Texarkana East

5210 Crossroads Pkwy, Texarkana, AR 71854

Phone: (870) 216-0083 http://www.texarkanaeasthotel.com

ANPS has reserved a block of 30 rooms (25 double queens and 5 kings) at the reduced rate of $89.00 plus tax per night. This rate includes high-speed wireless internet and a hot breakfast each morning. Reservations must be received by September 26, 2014 to guarantee the reduced rate. Be sure to mention that you are attending the Arkansas Native Plant Society meeting when making your reservation.

Several other hotels are located in the immediate area, including:

Comfort Suites – (870) 216-8084

Hampton Inn – (870) 774-4267

Best Western Plus – (870) 774-1534

Meals: Potluck snacks will be offered on Friday and Saturday evenings. Drinks will be provided by ANPS. Please feel free to bring a dish or snack to share. All other meals are on your own. Texarkana has many restaurant options, including well-known local spots such as Bryce’s Cafeteria and Cattleman’s Steakhouse, and a couple large grocery stores near the hotel.

Some notes about the field trips: We will provide full information about field trip locations on Friday evening.

Some of the prospective field trips are located in areas that have very few restaurant options. You may want to come prepared with lunch supplies in case we aren’t able to find a place to eat between the morning and afternoon walks on Saturday.

AGENDA

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 10

5:30-7:00 pm: REGISTRATION Public Welcome. Not a member yet? For more information about being a member of the Arkansas Native Plant Society click here.

Registration costs $5.00 per person and occurs in the Newcrest Meeting Room of the Holiday Inn and Suites. (No preregistration is required.)

Sign-up sheets for Saturday and Sunday field trips will also be available, along with descriptions of each trip.

7:00 pm: NATIVE PLANT AUCTION

The fall meeting begins with the annual native plant auction, which raises funds for our scholarships and grants program. This informal and fun auction features native plants grown by our members. Items such as books, seeds, plant presses, jams and jellies, and crafts are also often included in the auction. If you have something to donate, please bring it with you and give it to one of the meeting organizers to add to the auction.

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 11

8:30 A.M. Field trips depart from the hotel parking lot.

7:00 P.M: EVENING PROGRAM

Theo Witsell, botanist with the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, will talk on the subject, “Habitats and Rare Plants of Southwest Arkansas”.

Business Meeting will follow the evening presentation.

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 12

8:30 A.M. Field trips depart from the hotel parking lot.

ANPS Shirts: Remember, shirts are only available for sale at the spring and fall meetings. Please do not ask to reserve one or that we mail you one. We can’t. For more information about the ANPS Shirts, click here. (See website under About.)

Questions? Contact Jennifer Ogle at ranunculus73@gmail.com and 479-957-6859.

Please visit our website at http://anps.org

Know Your Natives – Starry and Wholeleaf Rosinweeds

Are They Sunflowers?

Rosinweeds (Silphium species) and sunflowers (Helianthus species) are in the Asteraceae (Aster) Family. Rosinweeds and sunflowers are herbaceous perennials with yellow composite flowers (ray florets with strap-shaped petals, disk florets with petals fused into small tubes) on top of tall rough stalks with simple leaves. Rosinweeds and sunflowers produce an odd assortment of flowers or florets, some fertile and some sterile, some of the fertile perfect (with functional male and female parts) and some of the fertile unisexual, that is, pistillate or staminate. For rosinweeds, ray florets are pistillate and fertile while disk florets are also fertile but functionally staminate, producing pollen but no seeds; however, for sunflowers, the ray florets are entirely sterile, producing neither seeds nor functional pollen, while disk florets are fertile and perfect, taking on all of the reproductive chores, and leaving the rays to look pretty and attract pollinators. For rosinweeds, styles of the pistillate ray florets are divided (bifurcate) as are the styles of the perfect disk florets of the sunflowers. The staminate disk florets of rosinweeds, in addition to the functional stamens, also have non-functional undivided styles-an uncommon character for the composites.

Starry Rosinweed Starry rosinweed (Silphium asteriscus), the “type species” (see footnote) for the Silphium genus, is found from Texas to Illinois to Virginia and southward to the Gulf. It grows throughout most of western and central Arkansas but infrequently in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. Plants grow naturally in prairies, meadows, open forests and woodlands, and roadsides. Plants three or more feet tall may have one or more stems. Stems feel rough to touch (scabrous) due to stiff hairs. Upright in sunny areas, stems in more shaded areas tend to recline. Starry rosinweed is drought tolerant. It is also a forage plant for deer. Leaf arrangement and characteristics change up-stem. Lowest leaves are opposite and lanceolate with the leaf base tapering into wings on long petioles. Higher up-stem, leaves are lanceolate, and become sessile and alternate with rounded bases. Lower leaves may be 6 inches or more long and 1.5+ inches wide. Upper and lower leaf surfaces are scabrous, the lower surface less so. Leaf edges, often mostly entire, may occasionally have widely spaced small teeth. Flower heads, singly or in one or several compact panicles, typically consist of 10+ fertile ray florets and a central disk of 30+ staminate disk florets. Bracts, forming an involucre of two or three layers, are acutely triangular, spreading, recurved, and overlapping (imbricate). Peduncles and involucre are covered with numerous stiff, spreading hairs (hirsute). Yellow ray petals, long and narrowly elliptical, are notched at the end. Starry rosinweed flowers in late spring into summer.

Photo 1: Starry rosinweed in an open woods setting. Alternate leaves with branching for flowering.

Photo 2: Involucre of starry rosinweed. Note hirsute involucres.

Photo 3: Starry rosinweed. Note appearance of ray florets and disk florets.

Wholeleaf Rosinweed Wholeleaf rosinweed (Silphium integrifolium), aka entireleaf rosinweed or prairie rosinweed, occurs primarily from Alabama to Texas, north to South Dakota and the Great Lakes. In Arkansas, it occurs more or less throughout the state. Wholeleaf rosinweed is found in dry tall-grass prairies, mesic prairies and rocky or dry open woods and glades. It is drought tolerant. It is also a forage plant for deer. Wholeleaf rosinweed reaches three to six feet in height and, with age, has many stout stems. Younger stems appear fuzzy and are scabrous, but roughness may disappear with age. Stems of plants in shade are green while those in sun are often purplish. Opposite, sessile leaves, up to 5 inches long and 2.5 inches wide, are broadly lance-shaped to ovate and are entire or slightly toothed. Leaves, which are medium green, are scabrous on top, but less scabrous on lower surfaces. Paired leaves are decussate (leaves rotated 90° from one pair to next). Flowering, occurring in mid-summer, produces panicles with flower heads 2 to 3 inches across. Twelve to 25 yellow ray florets surround numerous yellow disk florets. Yellow rays, long and narrowly elliptical, are notched at the end. Bracts, forming the imbricate involucre, are broad with very short hairs.

Photo 4: Wholeleaf rosinweed with opposite, decussate leaves and purplish stems.

Photo 5: Wholeleaf rosinweed with flowers in bud, in bloom, and past bloom. In flower past bloom, note winged achenes partially visible around infertile disk.

Photo 6: Wholeleaf rosinweed. Note divided styles of ray florets and stamens and

non-functional undivided styles extending from disk florets.

Footnote: “Type species” is a species that exhibits characteristics that define a genus and serves as a reminder of what is meant by a particular genus. Should a genus be divided, the type-species retains the original generic name.

Article and photographs by ANPS member Sid Vogelpohl

Posted in Know Your Natives, Native Plants, Wildflowers

Tagged Asteraceae, Helianthus, Rosinweeds, Silphium

1 Comment

Hummingbird Enjoying Obedient Plant

Know Your Natives – Starry Campion

Starry campion (Silene stellata) of the Caryophyllaceae (Pink or Carnation) Family is found throughout the eastern United States from North Dakota and Texas, eastward to the Atlantic Coast. In Arkansas, starry campion is found throughout the Interior Highlands (Ozark Mountains, Arkansas Valley and Ouachita Mountains), as well as on Crowley’s Ridge. It occurs in light shade or partial sun in both upland and lowland woods, savannas, prairies and on stream banks, in soils ranging from moist (mesic) to dry (xeric) loam and clay-loam with or without rocks.

Starry campion, aka widow’s frill, is an herbaceous, loosely-branched perennial plant that grows one to three feet tall. Plants consist of one or multiple stems arising from the crown of a thick, branched root-stock. The stems are branched only within the inflorescence. Lower portions of the stems are purplish, becoming less purplish above, though retaining the purplish color at leaf nodes. Elsewhere, the round stems are pale green and hairless to short, soft hairy. Stems with inflorescences often tend to lean, unless supported.

Leaves are opposite near the ground and in whorls of four higher up the stem and into the inflorescence. They are sessile (no petiole), acuminate (taper to a point), lance-shaped to elliptic, and entire (smooth margins). The leaves, up to four inches long and one and a half inches wide, have an upper surface that is medium green and glabrous (hairless) while the lower surface is paler and glabrous to finely pubescent (with soft hairs).

The inflorescence of starry campion, a terminal pyramidal panicle, consists of a main stem and a number of irregularly spaced branches carrying one to six or more flowers per branch. Branches arise first from above whorled leaves near the top of the plant, then above paired leaves higher up and then, at the very top, flowers occur individually. Flowers open across the entire inflorescence simultaneously (rather than strictly from top to bottom or vice versa), with some buds delayed for an extended bloom. Flowers (up to ¾” wide) open in the evening and close with bright sun. They have five white petals; three white, wispy, hair-like styles; ten white, hair-like stamens; and a light green bell-shaped calyx (formed by fused sepals) with five broad, often flaring, triangular points around the rim (giving a star-like appearance). Petals, deeply fringed in the flared upper portions, remain flared into the calyx, where they quickly taper to stalk-like bases. Calyxes are light green and hairless to finely pubescent on the outside and are marked with 10 darker green lines. They conceal a round, stalked ovary. Petals and stamens are attached below the stalked ovary (ovary in superior position). Smooth, green, rounded but flattened capsules (about twice the size of a BB) develop within the loosely enveloping calyxes. Capsules, maturing in late summer, contain up to about 20 small kidney-shaped seeds attached to a central placenta.

Starry campion is a good candidate for a native plant garden. It adapts well to a partly sunny site with good drainage and can survive dry periods. Early spring growth and white flowers in early summer are eye-catching. Its whorled leaves, fringed white petals, notable calyx, and considerable height provide interesting structure. In a small space it may need support. Starry campion propagates by seed only and is not invasive.

Note: Three other species somewhat similar to starry campion and found in northern Arkansas are white campion (Silene latifolia), bladder campion (Silene vulgaris) and ovate-leaf catchfly (Silene ovata). All three lack whorled leaves. White campion and bladder campion are introduced species and do not have fringed petals. Ovate-leaf catchfly is native, has narrower fringed petals and broad, opposite leaves.

Photo 1: Early spring. Erect stems of starry campion with near-ground opposite leaves and whorled leaves higher up.

Photo 2: Early summer. Clasping leaves located just below swollen nodes. Stem and nodes purple, but change to green higher up stem.

Photo 3: Flowers of each stem are in a loose terminal panicle.

Photo 4: Buds and flowers of starry campion at various stages of development on same branches.

Article and photographs by ANPS member Sid Vogelpohl

Posted in Know Your Natives, Native Plants, Wildflowers

Tagged Caryophyllaceae, Silene, Silene stellata, Starry campion

1 Comment

Know Your Natives – Wild Yam

Wild Yam (Dioscorea villosa) of the Dioscoreaceae (Yam Family), occurs from Texas to Nebraska to Minnesota and states eastward to the Atlantic Coast. In Arkansas, wild yam occurs statewide. The plant, a monocot (one seed leaf), is a twining vine which prefers a moist habitat, but will also grow in drier areas. Wild yam grows in a wide variety of habitats, ranging from borders of swamps, marshes, and lakes; to river and stream terraces; to open woodlands and savannas; moist, rocky, forested slopes; fencerows; and cleared easements. Preferring light sun to partial sun, it can survive in heavier shade, but it is less likely to flower. This deciduous, non-woody perennial grows from a thick rhizome which has been used for medicinal purposes.

A mature wild yam plant in the spring can stand freely (three or more feet) until it reaches support to twine around. Multiple stems typically emerge from a single rhizome; some stems occasionally branch. Spring growth matures to slender stems without tendrils or stem rootlets. Wild yam climbs upward and outward seeking sufficient sunlight to spread out its leaves and to flower. Height of plants tends to be seven feet or less as determined by age and availability of sunlight; however, length may sometimes reach 15 or more feet. Stems are hairless (glabrous), varying from reddish with spring growth, then to green and yellow in fall. Young, vigorously growing spring growth tends to be angular or narrowly ridged in cross-section, becoming round as stems mature.

Leaves of wild yam are fairly uniform, but leaf arrangement varies on a plant and from plant to plant. Generally, whorls of five to six leaves are found near the base of the stem, with whorls of decreasing number of leaves extending up the stem, to the point that leaves sometimes become opposite but then eventually alternate toward the end of the vine. Leaves are narrowly cordate (heart-shaped) to more broadly cordate with smooth margins and palmate veins (radiating from central point). Veins (7-11 veins per leaf) extend from petiole attachment toward leaf margins and apex in an arcuate manner. The upper leaf surface is medium green and glabrous, while the lower surface is pale green and may be covered with sparse or dense short hairs (the epithet “villosa” meaning “hairy”). Slender petioles, which may be as long as the leaf blades, hold leaf blades upright for maximum sun exposure.

Wild yam is dioecious (male and female flowers occur on separate plants). Flowers develop in early summer from leaf axils. Male flowers, occurring in panicles four to twelve inches long, are arranged in small clusters of two to three flowers along branches. A male flower, about 1/8″ across, consists of six whitish to yellowish-green sepals and stamens. Five to 15 female flowers are widely and individually spaced along dangling racemes that may be three to nine inches long. Female flowers, about 1/8″ across and 1/3″ long, consist of six whitish to yellowish-green sepals and a large inferior ovary with infertile stamens.

Female flowers are replaced by three-celled, strongly angled (or winged), ovoid capsules that usually contain two seeds or one seed per cell. The capsules become golden-green and then brown with maturity and may remain on the plant into the following spring. Flattened seed have broad wings suitable for wind dispersal.

Notes: Wild yam (Dioscorea villosa) is the only native yam currently recognized in Arkansas. However, some authorities have recognized whorled wild yam (Dioscorea quaternata) as distinct from the aforementioned species based on variations in leaf arrangement, cross-section of stems, and appearance of rhizomes. Also found in Arkansas is cinnamon vine or Chinese yam (Dioscorea polystachya), a non-native invasive plant now especially common on stream and river terraces throughout the upland areas of the state. Cinnamon vine grows from a tuber and has cordate to fiddle-shaped leaves which are usually alternate (sometimes opposite and very infrequently whorled). The majority of cinnamon vines naturalized in North America are male, thus sexual reproduction is rare. However, cinnamon vine spreads vegetatively via small, aerial bulbils (tubers) produced in the leaf axils, which are readily distributed by water.

Photo 1: Early spring growth of wild yam. Note whorled leaves and smooth stems lower on plant and reddish stem at top of photo (see in Photo 2).

Photo 2: Upper stems of a female wild yam plant. Note that upper portions are ridged, but becoming round as stem matures. Flowers developing in leaf axils.

Photo 3: Flowering male wild yam supported by black gum and poison ivy.

Photo 4: Flowering female wild yam supported by sassafras. Note characteristic leaf shape and venation.

Photo 5: Female wild yam with developing seed capsules.

Photo 6: Immature wild yam plant showing only basal leaves. NOTE: At this stage, may be confused with species in the Smilax genus, such as carrion flower (Smilax lasioneura) .

Article and photographs by ANPS member Sid Vogelpohl

Posted in Know Your Natives, Native Plants, Vines

Tagged Dioscorea, Dioscorea villosa, Dioscoreacea, Wild yam

Leave a comment

Know Your Natives – Texas Dutchman’s-Pipe and Virginia Snakeroot

Texas Dutchman’s-pipe (Aristolochia reticulata) and Virginia snakeroot (Aristolochia serpentaria) are non-woody woodland perennials of the Aristolochiaceae (Birthwort) Family. Mature plants can consist of a bundle of a few to numerous stems to 18 inches tall and bearing alternate leaves. Stems are fairly uniform in size from top to bottom, but swollen at leaf junctions and becoming zigzag from leaf to leaf toward the top. Leaf size is generally greatest mid-stem, tapering smaller toward the stem base and tip . Plants are seen from early spring into late fall, but disappear above ground in winter. Plants tend to occur singly and in limited numbers.

Short, weak flowering stems, which grow from the base of plants in mid-spring, are partially hidden by leaf litter. Flowers are purplish to reddish with a tubular S-shaped calyx (corollas are absent), a shape characteristic of the genus. Pollinator flies are trapped in the base of flowers by the constricted neck and inward-pointing nectar-bearing hairs until stamens mature (stigmas mature before stamens). When stamens have matured, hairs wilt and flies leave carrying pollen to fertilize other plants.

Seeds form in round capsules that split into six segments at maturity in early summer. Seeds have no means of self-transport and thus are released at the plant’s base. Seeds are rounded and somewhat flattened, with tiny papillae (bumps or wrinkles) on the outside surface. Seed dispersal is by birds and small mammals.

Texas Dutchman’s-pipe and Virginia snakeweed are important host plants for pipevine swallowtail butterflies. By ingesting aristolochic acids in the plants, caterpillars and butterflies become unpalatable to predators. (Adults of several other butterfly species mimic the appearance of pipevine swallowtails for their own defense.)

Texas Dutchman’s-pipe

Texas Dutchman’s-pipe is found in Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas and Louisiana. In Arkansas, it is found in scattered counties in the northwest, southwest and central portions of the state. Plants grow in well-drained, rocky or sandy woodlands in partially shady to mostly sunny areas. The entire plant is covered with short hairs. Elongated, ovate to heart-shaped, thick leaves are deeply veined on top and deeply ribbed below. The leaf surface between veins is flexed, giving the surface a rough-textured appearance. The leaves appear to be perfoliate, but are actually on short petioles with lobes of the leaf bases wrapping around the stem. The edges of leaves are entire and the apex is obtuse to rounded. Each flowering stem has several flowers with each flower on a separate branch.

Photo 1: Texas Dutchman’s-pipe in mid-spring.

Photo 2: Caterpillars of pipevine swallowtail on Texas Dutchman’s-pipe.

Photo 3: Flowers of Texas Dutchman’s-pipe.

Virginia Snakeroot

Virginia snakeroot, once used to treat snake bites, occurs from Texas to Iowa and eastward to the Atlantic. In Arkansas, it occurs statewide. Plants grow in moist, well-drained woodlands in shady to lightly sunny areas. The non-hairy stems may be branched near the base. The stems of Virginia snakeroot are thinner and weaker than Texas Dutchman’s-pipe and may recline on the ground (decumbent). The thin, slightly shiny, elongated to linear, heart-shaped, non-hairy leaves are on long petioles. The lobes at the base of the leaves are flared toward the stem. The edges of leaves are entire and the apex tapers gradually to a long, pointed tip. Each flowering stem has one flower.

Photo 4: Virginia snakeroot in mid-spring.

Photo 5: Flowers of Virginia snakeroot.

Photo 6: Drying seed capsules of Virginia snakeroot.

Articles and photographs by ANPS member Sid Vogelpohl

Know Your Natives – “Leaves of three, let it be”…usually

We have all heard the advice, “Leaves of three, let it be”. Two native Arkansas plants, poison-ivy and poison-oak, have three leaflets per leaf and contain urushiol, an oily allergen. Following direct or indirect contact, many people experience allergic reactions (contact dermatitis) resulting in skin redness, itching, swelling, and blisters, with severity being dependent on an individual’s sensitivity. Urushiol is water soluble so it can be removed from skin with soapy water, with less or no irritation if done within about 15 minutes.

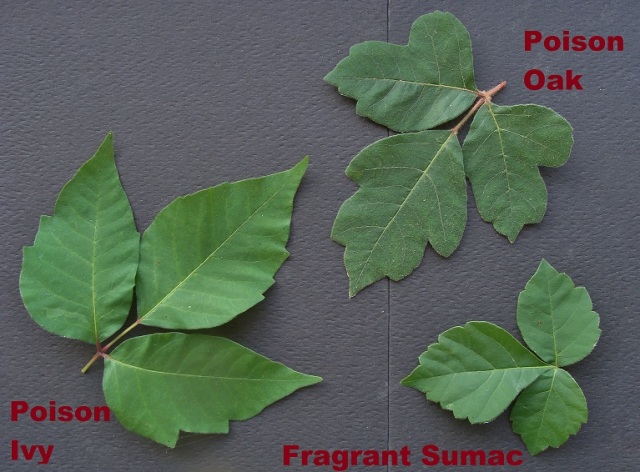

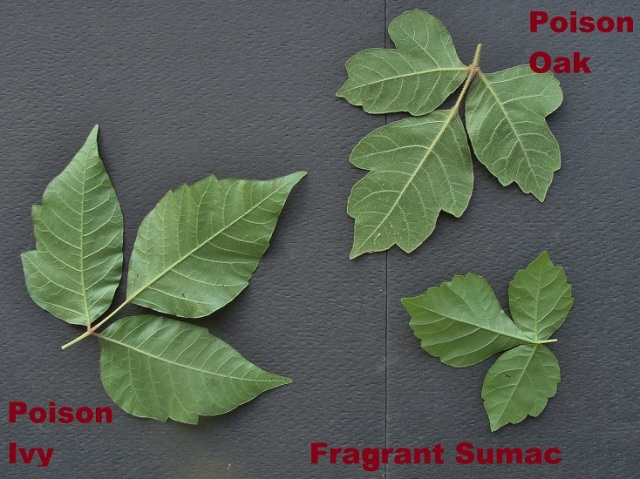

For those hiking or gardening, being able to recognize poison-ivy and poison-oak is important, so that such activities can be better enjoyed. Growth habits of these two plants is such that one or both plants could be encountered anywhere from foot-level to head-level. Both poison-ivy and poison-oak have a leaf characteristic which helps distinguish them from other plants with three leaflets per leaf. As shown by Photos 1 and 2, that characteristic is the presence of a petiolule (the stalk of an individual leaflet, as opposed to a petiole, the stalk of a whole leaf) at the base of the terminal leaflet.

Fragrant sumac, which has a sessile (no petiolule) terminal leaflet, is also shown in Photos 1 and 2. It grows in similar habitats as its cousins poison-ivy and poison-oak and has leaves that look similar and may often be confused with its more notorious relatives. However, fragrant sumac does not cause contact dermatitis in most people.

Poison-ivy, poison-oak, and fragrant sumac are all deciduous plants of the Anacardiaceae (Cashew) Family. Leaves of these three plants vary in shape, venation and texture. Leaf size is also somewhat variable, more so in poison-ivy which may have leaves up to two feet long, especially when the plant vines. All three plants produce drupes (berry-like fruits with a fleshy outer layer covering a hard inner shell surrounding the seed) that are important to wildlife. All have nice fall color.

Photo 1: Upper leaf surfaces of poison-ivy, poison-oak, and fragrant sumac. (Leaf stems removed for photo.)

Photo 2: Lower leaf surfaces of poison-ivy, poison-oak, and fragrant sumac. (Leaf stems removed for photo.)

Poison-Ivy

Poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), a woody vine, occurs throughout Arkansas. Plants may trail along the ground, but can be sufficiently self-supporting to have upright stems several feet tall with a shrubby appearance. Poison-ivy will attach itself to a tree trunk via numerous strong rootlets and grow quickly toward brighter light. Vines of varying sizes, up to five inches in diameter, may surround a tree trunk and remain strongly rooted to the tree. Older plants may grow 60 feet or more from the ground and, nearer the ground, have many horizontal limbs growing in all directions from the tree trunk, extending out for up to six feet. Poison-ivy has smooth, white drupes that mature in the fall.

Photo 3: Poison-ivy with inflorescence. Photo taken May 22nd.

Poison-Oak

Poison-oak (Toxicodendron pubescens, formerly Toxicodendron toxicarium), is a woody shrub that exhibits limited branching and may grow to four feet tall (see Photo 4). It also may trail along the ground somewhat but does not typically vine up other vegetation. Poison-oak is found throughout much of Arkansas, though is mostly absent from the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. Poison-oak usually occurs in sandy to rocky soils in drier woodlands and pinelands. Leaflets of poison-oak are usually hairy, unlike poison-ivy, and have rounded lobes somewhat resembling those of some species of oaks. Poison-oak has small, smooth yellowish drupes that mature in the fall.

Photo 4: Poison-oak with dried inflorescence. Photo taken May 24th.

Fragrant Sumac – A Poison-Ivy/Poison-Oak Look-Alike

Fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica), a low-growing woody shrub (see Photo 5), is found throughout most of Arkansas. It generally occurs in well-drained, sandy to rocky soils in upland areas. Fragrant sumac occurs in dense stands of smooth, unbranched stems arising from root suckers. Plants have a slow growth rate, typically reaching two to four feet tall, but some varieties can reach six feet tall with a spread of up to 10 feet. Leaflets are usually hairy and have rounded lobes. One-inch catkins (male) and short panicles (female) in a cluster on twig tips form on separate plants (sometimes on same plant) at the ends of stems. Catkins form in late summer, but don’t open until early spring. The more common variety blooms before the plant leafs out, but another variety more common in the limestone areas of the Ozarks flowers as or after the leaves appear. Hairy red drupes of fragrant sumac mature in late spring. The leaves and stems have a citrus-like fragrance when crushed (this test not recommended for poison-ivy or poison-oak).

Photo 5: Fragrant sumac with fruit. Photo taken May 12th.

Additional notes: Smooth sumac (Rhus glabra) and winged sumac (Rhus copallina), both common in Arkansas, are non-allergenic. Unlike fragrant sumac, these two sumacs would not be confused with poison-ivy or poison-oak since they have pinnately compound leaves. Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), which also has pinnately compound leaves, fortunately does not occur in Arkansas. Some other native plants may also be confused with poison-ivy or poison-oak, such as marine-ivy (Cissus trifoliata, formerly Cissus incisa) and hop tree (Ptelea trifoliata) which also have three leaflets, but, like fragrant sumac, these two have sessile terminal leaflets.

“Leaves of three, what can it be?”

Article and photos by ANPS member Sid Vogelpohl

Know Your Natives – Four-Leaved Milkweed

Milkweeds, of the Apocyanceae (Dogbane) Family (formerly of the Asclepiadaceae [Milkweed] Family), are herbaceous perennials with 14 species identified in Arkansas. Most, but not all, milkweeds have milky sap. Milkweeds are important pollinator plants attracting butterflies, moths, ants, bees, flies, and wasps. The life cycle of Monarch butterflies depends on milkweed (Photos 1 and 2). Migratory milkweed bugs are dependent on the plant juices sucked from immature seed pods (Photo 3).

Photo 1: A travel-worn Monarch laying an egg on whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata)

Photo 2: Monarch butterfly caterpillar eating milkweed seedpod of butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Photo 3: Adult and young milkweed bugs on outside of dried milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) pod. Note seed with hairs at lower left.

Milkweeds have a unique floral structure. Milkweed flowers, arranged in round or flat clusters (umbels), do not have stamens with typical filaments and anthers or pistils with a typical stigma at top. Instead, five strongly reflexed sepals and petals surround a bizarre central structure of five anthers fused to a stigma head. To make matters more complicated, a corona (or crown) of five nectar-bearing hoods projects from the base of this structure. In most species of Asclepias (milkweed), each hood bears a curved horn (Photo 4). The horns may cause an insect to pause longer to withdraw nectar. Pollen grains are cemented into ten packets, called pollinia, located on either side of five prominent stigmatic slits. Pollinia are connected in pairs by threadlike, wiry structures to a “clip” that sits at the top of each slit. Bees and other insects occasionally lift a “spiny” foot through the slit to the clip, so that foot and clip become entangled. In removing the foot, the clip with its pair of pollinia is also removed. When the insect’s foot inadvertently slips into the slit of another flower, one of the pollina may be left behind and pollination is effected. You can try your own skill at this elaborate pollination system with a milkweed flower (the biggest one you can find) and a needle: place the needle point in the cleft of the clip at the top of a stigmatic slit and lift. The clip will come away carrying two tiny, yellow winglike packets of pollen with it–the pollinia.

Photo 4: Flowers of whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata) showing characteristic features of milkweeds

Seed pods enlarge from one or a few of the ovaries after the disposable parts of the flowers have fallen from the inflorescence. Pods may form a month or more after flowers have fallen and may remain on the plants for some time. Generally, few pods are formed on any one plant, but more than a hundred seeds may be in each pod. Flat, circular seed are tightly arranged in overlapping rows with white, silky, filament-like hairs (see Photo 3). When mature and dry, pods split longitudinally along a seam and seeds are tugged out by breezes and wafted aloft. Of course, those seed that provided food to the milkweed bug are not viable and seed produced in dry summers may also not be viable.

Four-leaved Milkweed

Four-Leaved Milkweed (Asclepias quadrifolia) (Photos 5, 6 and 7 ) is one of the first milkweeds to bloom in the Spring. It occurs from eastern Oklahoma and Missouri into Arkansas and in most states of the Midwest, Southeast and Northeast. In Arkansas, the species is found in the Ouachita and Ozark Mountains as well as in the highlands of the Arkansas River Valley. Habitat is dry to somewhat moist, rocky open woodlands. Plants have branched, shallow white rhizomes.

Among milkweeds, this species’ small stature is unusual. Plants are up to 2 feet tall, consisting of one or more erect, simple, smooth-looking stems with fine hairs and simple ovate to elliptic leaves. Lower portion of stem is purplish. Thin, long-pointed leaves on short petioles are opposite or alternate, but usually with one or two groups of three to four whorled leaves about mid-stem. Leaves, 1 to 5” long and ½ to 2½” wide, are entire. Sap is milky.

Flowers, approximately 15, in umbels on long, thread-like stalks may be terminal and/or lateral, so that several umbels may occur along the upper portion of the stem. Umbels typically are subtended by a pair of leaves and droop from the stem. Flowers are pink, sometimes almost white. Slender erect seed pods are about 5″ long.

Photo 5: Inflorescences of four-leaved mildweed appears with early growth

Photo 6: Flower umbels of four-leaved milkweed droop from the stem

Photo 7: Seed pods of four-leaved milkweed

Article and photographs by ANPS member Sid Vogelpohl

Report on trip to Mt. Kessler with Joe Neal on April 12

The day dawned absolutely gorgeous; it was a great day to go to Mt. Kessler. The area has been used for years by hikers and bicyclists and winds its way through Rock City, an area with large sandstone palisades sporting fossils to stop and admire, as well as newly emerged wildflowers. A number of broad winged hawks whose flight patterns and high pitched calls suggested they might be establishing territory for nesting were seen; one even perched on a bare branch where Joe Neal observed a small snake in its talons. A pair of blue-gray gnatcatchers had just about completed their nest, rimmed in lichens. The trail winds through a forest that supports sugar maples, as well as chestnut oaks that Dr. David Stahle of the University of Arkansas has identified as being >200 years old. The trail was made prettier by the blooming redbuds and black cherries. Present for the hike were Joe Neal, Joan Reynolds, Terry Stanfill, Deb Bartholomew, and Frank and Mary Reuter. The trail was busy with hikers and bike riders as well, though. Joan and I lagged behind the group, looking for all the newly emerged plants as a complete inventory will be conducted by Theo Witsell, starting later in the month. Joan was determined to document all those species that might not be around for Theo to observe in a few weeks, so we went slow! So slow, in fact, that we met our group coming back down the trail without having reached the anticipated shale slide that was our goal. But, the slow pace paid off. Joan spotted two large brain Gyromitra mushrooms, and a few trout lilies that looked suspiciously like prairie trout lily (Erythronium mesochoreum) that Theo has been finding at other locales this spring. Both Erythronium albidum (white trout lily) as well as Erythronium rostratum (yellow trout lily), once misidentified in Arkansas as E. americanum, have previously been documented on Mt. Kessler.

Plant list for Mt. Kessler April 12, 2014 OCANPS

Article by ANPS member Burnetta Hinterthuer